Mission Impossible: Performance Photography

Fade In POV (Camera Left)

Theme from Mission Impossible playing in the background. Cut to a pair of hands taking a cassette tape out of an envelope and placing it in a tape deck. (For those of you too young to remember what a cassette tape is, it was the predecessor of the CD and DVD). Bring down the music and cut to reveal that we are in a photography studio. We see the photographer push the playback button. As the wheels on the cassette turn, we hear:

“Good morning, Photographer. Imagine a situation where you cannot control the placement, amount or intensity of the light, where you cannot add to or modify what is there. Imagine mixed light sources that are constantly changing colors — a white balance and capture nightmare. Imagine a very limited space from which to shoot — in a place so crowded you cannot move. And, imagine subjects that are moving quickly in a very dynamic situation; what you want to capture will happen once, and then, in a moment, it will be gone; there will be no retakes or do overs; get it right or go home. Imagine rigorous time limits enforced by troops known as Security. And, finally, imagine the ultimate restriction — do not interfere, in any way, with what is going on around you, or block anyone’s view or enjoyment of the proceedings.”

Cut Away to Tight Shot of Tape Recorder

“Your mission, Photographer, should you decide to accept it — is to capture a performance. As always, should you or any of your crew fail, you will be up S. Creek without a paddle. Good luck. This tape will self destruct in ten seconds.”

Cut Away to a Shot of the Tape Recorder Going Up in Smoke

Performance Photography — The Common Challenges

A while back, I set out to learn about “concert photography” — that magic blend of passion and energy that explodes when band meets photographer. I took some classes at Photoshop World from two of the genres best, Alan Hess and Scott Diussa, interviewed Alan personally, and watched their superb series of lessons on Kelby Training.

What did I learn? That the challenges they face are no different than those I face when I photograph sports, or when I did my daughter’s band and color guard performances. In fact, they are the same challenges many of us face in doing everyday events like dance, theater and weddings. In essence, we are capturing live performances — in venues that, though they may differ, share the same issues.

Of course, it’s those issues that get the adrenaline flowing, that get our hearts beating, that put us into “fight or flight mode” — that make this type of photography both exciting and rewarding. Doing it right is a rush, and that’s why most of us do it.

And, as Alan and Scott point out, most of the people doing it are in it for the “rush” for their love of music, for their passion for photography — because very few can make a living at it. The economics just don’t work. But, that’s an article for another time.

Drawing on my own experience and what I’ve learned from Alan and Scott, I thought I’d work through some of those challenges and write about strategies for dealing with them.

Getting In

When shooting performances, access is everything. Getting in. Getting the right to shoot. Getting the right to use our images. Those are the first challenges we face.

Although they differ by genre and venue, there are some common issues.

First, be it a concert, club, or athletic performance, to get to into the photo pit, or on the field, you need someone’s permission — usually in the form of a “pass”.

A. To get a concert pass, Alan and Scott tell us to look to the performers, the owners of the venue, and/or the publicists for both. With professional sports like football, I’ve gotten my passes through the teams. With auto racing, the teams and sanctioning bodies. With high school sports or performances, the passes, in my area, are controlled by the school districts — although the initial contacts are made through the schools teams or bands; getting to know the coach, the band director, or someone on the staff is often the first step in getting a pass. Don’t know anyone? Make an appointment, introduce yourself, and show some of your images.

Some times, it’s easy to get a pass. Some performers and venues are flattered. Often, they will barter access for prints. The smaller the venue, the less known the performers, the greater the chance of getting our first chance to shoot.

B. Because “press pass” access is so cool, and so many people want it, with bigger events, it’s often much more difficult to get a pass. Big events have “press coordinators” who dole out a limited number of credentials to those who can prove they are “professional”. And, they don’t define professional by reference to the quality of our work. They want “working press” — photographers whose images are being “published” in some recognized media — be it a newspaper, magazine, a stock photo house, or a strong online presence. Often, their applications for a pass require a letter from the media outlet for whom we are shooting.

It’s Catch 22. To shoot a concert or event, you need a publisher. And, you can’t get a publisher until you’ve shot enough concerts and events to prove your mettle.

I faced that challenge when I wanted to shoot The United States Men’s Clay Court Championships at a local tennis venue. The application for a pass was rigorous — I had to have a letter from the editor of a publication that was “commissioning” my work. Hmm. OK, the Houston Chronicle had a staff full of photographers; they wouldn’t need me. The tennis magazines used the same people tournament after tournament. So did the strong online tennis sites. None of them were going to sponsor me. I was having a hard time figuring out who was.

One night, the answer showed up on my front lawn — in the form of a “throw away” newspaper. You, know, the kind that deal with local stuff and a lot of advertising. The kind that we normally put on the recycling pile without first reading it. But, this time I opened it up and noticed that it had a sports page. Local school sports but sports none the less.

So, I called the sports editor and made him a deal he could not refuse. If he would sponsor me, I’d give him a license to use whatever images I shot — but I’d keep the copyright. It was a good deal for both of us; he got images he’d not normally get and I got in and got to keep my copyright. We met, I showed him a portfolio of tennis shots I had captured, over the years, as a “spectator”. (The access to practice sessions is often unlimited. Those times are great for capturing some portfolio shots.)

The sports editor signed on. With his support I filled out my application. The tournament sponsor demanded some “sample shots”, too. I guess mine were good enough. I got my pass. And, based upon my work at that tournament, I got a pass for the next one, too.

I got access to shoot for the Texans by working as an assistant to one of their regular free lancers. He generously told me to bring my camera and encouraged me to shoot with him. I gave him my images and he turned them over to the Texans. Why did I give him my images? Because, this was his job; I was not going to compete with him in any way; I was there and shooting because he was being generous. A year later, he could not make a game and suggested they use me; unfortunately, I had a scheduling conflict. But, they know who I am and where I am should they ever need me, again.

The bottom line is that for many of us, getting that first press pass is the toughest challenge we will face. Our photography is good. We just need the access to the events that will take us to the next level. Two things got me where I wanted to go: a portfolio of the types of images I wanted a credential to shoot; and, finding an “off the beaten path” sponsors willing to work with me to our mutual advantage.

Want to break in — get those first portfolio shots? Don’t forget small clubs, high school bands, minor league or high school sporting events. They are a great place to develop skills and techniques.

I learned more about shooting performances by shooting under the Texas Friday Night Lights than I had shooting pro-football, big time auto racing, or the tennis tournaments. My access? My kid. For four years, Jen marched with the Memorial High School Band or performed with the Color Guard. They were thrilled to have me capturing their performances. Over those years, I shot thousands of images — learned to conquer the lighting issues, learned to cope with the speed with which things moved around me, and learned to hone my post production processing so as to do it right, quickly. And, there was something very special about being there. As good as the movie and TV series were — and they were very good — Friday Nights in Texas are bigger than life. You really have to experience it to understand it. And, if you can experience it, you should.

Staying In

So, now we’re in the door. How do we stay in? Three things — follow the rules, play nice, and use common sense.

Every pass comes with a set of rules. Depending on the venue and/or event, we are usually told where we can be, how long we can be there, what we can shoot, and how we can use the images.

A. It appears that the concert photographers like Scott and Alan are the most severely restricted. First, and foremost is the “3 song rule” — the rule that says “You can shoot the first three songs of the concert and then you must pack up and leave.” This rule is not always in effect — but it usually is. What it means is simple — you shoot the first three songs of the concert, pack up and leave. You do not try to stretch the time limit by one note. If you do, security will usually remove you and you will get a reputation that makes it difficult to get another pass.

When you are shooting a sports event, there are almost always strict “location” restrictions that keep you a set distance away from the playing field or, in auto racing, places on the track where you can and cannot be. Strict location rules are enforced for two reasons — first and foremost safety (yours and the players) and, second, protecting the audience’s view of the event. Similar rules apply in concert venues where photographers share a “pit” — a small area right in front of the stage.

B. Another strict rule — we can only shoot “available light”. No flash. No enhancement. Camera only. The reason is obvious — yet I’ve seen people using flashes shot directly at players’ eyes; fortunately, most are shot from distances so great that, with the “fall off” of light, they have no impact on the players (or the image). Mounting a flash on your camera usually sends the message “I don’t belong here” a message that will get one noticed and excluded. (That does not mean you should leave your flash at home — just don’t use it during the performance. If you get lucky enough to be invited back stage, or end up covering a press conference or interview, you may be able to use it.)

C. A “Gotcha”: We cannot assume that we own the images we shoot. Or, that we can do as we please with them. Alan and Scott make clear that to get access to shoot a concert, many photographers sign away all of their intellectual property rights to the images. And, sometimes the restrictions are more severe. It is possible to shoot a concert and walk away completely empty handed — without an image to post on one’s own website. So, it is essential to read all of the documents that are associated with getting the permit and to understand the promises you are making. Because, those promises are a binding contract.

Want to own the copyright and/or have images to use? Often, the smaller venues and less known performers do not have the more restrictive agreements. In those cases, we can use our own “releases” to create the relationships.

It is very important that we not confuse the right to “access” with the “releases” we need to use the images of people or places. The right to be there is different from the right to exploit the images. The person who controls the “pass” does not always control the performer, player, or audience members’ right to the exploitation of their person. Sometimes, the players/performers sign releases to the promoters who can assign them to us. Other times, they don’t. And, those crowd shots that we love? We may need releases to exploit them. Buying a ticket or attending a performance does not always constitute a release for our purposes.Finally, the club owners may have a right to control the exploitation of images of the venue. Actually, the right to privacy and to control the use of one’s image or property is a topic far beyond this post. But, I wanted to raise the topic. We all have to think about it and seek the proper advice before we start publishing our images shot at events.

D. So much for the formal rules. Perhaps, the greatest rule is Play Nice. Cooperate with the other people shooting the event. Scott and Alan make clear the concert ethic — work around people without interfering AND once you get your shot, move so that others can get the access and angle they need. One of the great things on their video is a segment where we see the almost dance like “choreography” as they photographers seamlessly work around each other — each moving to open a spot for another.

Nothing says “Amateur” more than someone who just grabs a spot and hogs it for the entire performance. One of my favorite Texas sayings: “Pigs get fat. Hogs get slaughtered.” This is a cooperative effort. If we are hogs, if we do not cooperate and play nice — we won’t get a chance to make the effort again.

Another part of “playing nice” is to make sure we do not become a part of, or interfere with, the event.

Inadvertently, I’ve stumbled a bit here. Jen’s band was in a district competition. I shot the “dress rehearsal” which was being recorded on audio tape. I tried to be as unobtrusive as I could. I found a spot that put me out of the line of sight of the kids and their teacher. I had my long lens — so I was an appropriate distance so as not to block the audience’ view. But, I didn’t look up. I should have. Because 5′ above my head was a one of the recording microphones. A chagrined Jenny told me during the break before their real performance: “Daddy, we can hear your shutter on the tape!” Ugh! My bad. Learned my lesson — whenever I’m shooting in an environment with recording equipment, I look for the microphones and stay away from them.

And, then there was the time that I was out on the field during the band and guard’s half time performance. Jenny told me that I got in the way of the drum line and made them break formation by a step to get around me. I did not make that mistake, again, either. How did I avoid it? Research.

Research and Preparation:

One of the strongest points that Alan and Scott make is that we have to do our homework.

They listen to the band they will be shooting — know the music, and how it is performed. They watch videos, read interviews, do whatever they can to totally understand how the songs will be played and how the stage will be used. One of the things I found most fascinating about their lessons was the detail to which they go to set themselves up to use those three songs productively. By knowing the music, they will know where a guitar player’s hands will be during a riff — which will often allow them to get a coveted “two hand” shot. The microphone is the enemy of most concert shooters. It blocks the face or casts ugly shadows. But, they’ve learned that some singers pull away from the mic when they hold long notes — a great time to get that close head shot; knowing when the long held notes will come, they are in position and ready to get the shot. How do they get so much done within the short time period delimited by the “three song rule”? Research and preparation. They know what they want and when they are likely to get it.

After my “Daddy! You made the drum line move!” event, I started doing the same thing. I had Jenny teach me the choreography — where people would be and when. From that point on, every time I stepped on that field with my camera I knew exactly what I wanted to get and where I could go to get it WITHOUT interfering with the performance. I got better shots and Jenny got to relax.

In a like manner, we have to prepare to shoot sports. It’s not by happenstance that the same photographers always seem to get the “money shots”. It’s preparation. They know their sports and the people who play them. On a tennis court, there are very limited places where we can sit or kneel to shoot. Knowing the players, whether they play a “net” or “baseline” game makes a huge difference. On most race tracks, there are very few places where cars can actually pass each other; to capture the excitement of that competition, one must be able to get those places in the frame. In football, knowing what a team is likely to do on a 3rd and 5 will improve the odds of getting a great shot. But, even with the best preparation, there is still a great bit of luck involved in being in the exact right place at the right time. Preparation narrows the risks but does not guarantee a result. But, I’ll go along with one of my trial lawyer friends who likes to say “Isn’t it funny that the people who prepare the most are always the “luckiest”.

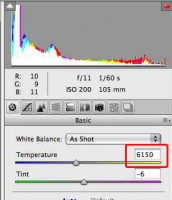

Because this post is running long, I’m breaking it into two parts. Part II will focus on equipment and lighting issues. To get to Part II, click here.

(Copyright: PrairieFire Productions/Stephen J. Herzberg — 2011)

Leave a Reply